Part 1

Read the text and answer questions 1-13.

Part 2

Read the text and answer questions 14-26.

Part 3

Read the text and answer questions 27-40.

Bricks – The Versatile Building Material

Bricks are one of the oldest known building materials dating back to 7000 BCE. The oldest found were sun-dried mud bricks in southern Turkey and these would have been standard in those days. Although sun-dried mud bricks worked reasonably well, especially in moderate climates, fired bricks were found to be more resistant to harsher weather conditions and so fired bricks are much more reliable for use in permanent buildings. Fired brick are also useful in hotter climates, as they can absorb any heat generated throughout the day and then release it at night.

The Romans also distinguished between the bricks they used that were dried by the sun and air and the bricks that were fired in a kiln. The Romans were real brick connoisseurs. They preferred to make their bricks in the spring and hold on to their bricks for two years, before they were used or sold. They only used clay that was whitish or red for their bricks. The Romans passed on their skills around their sphere of influence and were especially successful at using their mobile kilns to introduce kiln-fired bricks to the whole of the Roman Empire.

During the twelfth century, bricks were introduced to northern Germany from northern Italy. This created the 'brick Gothic period,' which was a reduced style of Gothic architecture previously very common in northern Europe. The buildings around this time were mainly built from fired red clay bricks. The brick Gothic period can be categorised by the lack of figural architectural sculptures that had previously been carved in stone, as the Gothic figures were impossible to create out of bulky bricks at that time.

Bricks suffered a setback during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, with exposed brick walls becoming unpopular and brickwork being generally covered by plaster. Only during the mid-eighteenth century did visible brick walls again regain some popularity.

Bricks today are more commonly used in the construction of buildings than any other material, except wood. Brick architecture is dominant within its field and a great industry has developed and invested in the manufacture of many different types of bricks of all shapes and colours. With modern machinery, earth moving equipment, powerful electric motors and modern tunnel kilns, making bricks has become much more productive and efficient. Bricks can be made from a variety of materials, the most common being clay, but they can also be made of calcium silicate and concrete.

Good quality bricks have major advantages over stone as they are reliable, weather resistant and can tolerate acids, pollution and fire. They are also much cheaper than cut stonework. Bricks can be made to any specification in colour, size and shape, which makes them easier to build with than stone. On the other hand, there are some bricks that are more porous and therefore more susceptible to damage from dampness when exposed to water. For best results in any construction work, the correct brick must be chosen in accordance with the job specifications.

Today, bricks are mainly manufactured in factories, usually employing one of three principal methods – the soft mud process, the stiff mud process and the dry clay process. In the past, bricks were largely manufactured by hand, and there are still artisanal companies that specialise in this product. The process involves putting the clay, water and additives into a large pit, where it is all mixed together by a tempering wheel, often still moved by horse power. Once the mixture is of the correct consistency, the clay is removed and pressed into moulds by hand. To prevent the brick from sticking to the mould, the brick is coated in either sand or water, though coating a brick with sand gives an overall better finish to it. Once shaped, the bricks are laid outside to dry by air and sun for three to four days. If these bricks left outside for the drying process are exposed to a shower, the water can leave indentations on the brick, which, although not affecting the strength of the brick, is considered very undesirable. After drying, the bricks are then transferred to the kiln for firing and this creates the finished product. Bricks are now more generally made by manufacturing processes using machinery. This is a large-scale effort and produces bricks that have been fired in patent kilns.

Today's bricks are also specially designed to be efficient at insulation. If their composition is correct and their laying accurate, a good brick wall around a house can save the occupants a significant amount of money. This is primarily achieved today through cavity wall insulation. Insulating bricks are built in two separate leaves, as they are called in the trade. The gap between the inner and outer leaves of brickwork depends on the type of insulation used, but there should be enough space for a gap of twenty millimetres between the insulating material in the cavity and the two leaves on either side. The air in these gaps is an efficient insulator by itself. Cavity walls have also replaced solid walls, because they are more resistant to rain penetration. Because two leaves are necessary, a strong brick manufacturing industry is essential, so that enough good quality insulating bricks are plentifully available.

We have Star performers!

A The difference between companies is people. With capital and technology in plentiful supply, the critical resource for companies in the knowledge era will be human talent. Companies full of achievers will, by definition, outperform organisations of plodders. Ergo, compete ferociously for the best people. Poach and pamper stars; ruthlessly weed out second-raters. This, in essence, has been the recruitment strategy of the ambitious company of the past decade. The 'talent mindset' was given definitive form in two reports by the consultancy McKinsey famously entitled The War for Talent. Although the intensity of the warfare subsequently subsided along with the air in the internet bubble, it has been warming up again as the economy tightens: labour shortages, for example, are the reason the government has laid out the welcome mat for immigrants from the new Europe.

B Yet while the diagnosis – people are important – is evident to the point of platitude, the apparently logical prescription – hire the best – like so much in management is not only not obvious: it is in fact profoundly wrong. The first suspicions dawned with the crash to earth of the dotcom meteors, which showed that dumb is dumb whatever the IQ of those who perpetrate it. The point was illuminated in brilliant relief by Enron, whose leaders, as a New Yorker article called 'The Talent Myth' entertainingly related, were so convinced of their own cleverness that they never twigged that collective intelligence is not the sum of a lot of individual intelligence. In fact, in a profound sense, the two are opposites. Enron believed in stars, noted author Malcolm Gladwell, because they didn't believe in systems. But companies don't just create: 'they execute and compete and coordinate the efforts of many people, and the organisations that are most successful at that task are the ones where the system is the star'. The truth is that you can't win the talent wars by hiring stars – only lose it. New light on why this should be so is thrown by an analysis of star behaviour in this months' Harvard Business Review. In a study of the careers of 1,000 star-stock analysts in the 1990s, the researchers found that when a company recruited a star performer, three things happened.

C First, stardom doesn't easily transfer from one organisation to another. In many cases, performance dropped sharply when high performers switched employers and in some instances never recovered. More of success than commonly supposed is due to the working environment – systems, processes, leadership, accumulated embedded learning that are absent in and can't be transported to the new firm. Moreover, precisely because of their past stellar performance, stars were unwilling to learn new tricks and antagonised those (on whom they now unwittingly depended) who could teach them. So they moved, upping their salary as they did – 36 per cent moved on within three years, fast even for Wall Street. Second, group performance suffered as a result of tensions and resentment by rivals within the team. One respondent likened hiring a star to an organ transplant. The new organ can damage others by hogging the blood supply, other organs can start aching or threaten to stop working or the body can reject the transplants altogether, he said. 'You should think about it very carefully before you do a transplant to a healthy body.' Third, investors punished the offender by selling its stock. This is ironic since the motive for importing stars was often a suffering share price in the first place. Shareholders evidently believe that the company is overpaying, the hiree is cashing in on a glorious past rather than preparing for a glowing present, and a spending spree is in the offing.

D The result of mass star hirings as well as individual ones seems to confirm such doubts. Look at County NatWest and Barclays de Zoete Wedd, both of which hired teams of stars with loud fanfare to do great things in investment banking in the 1990s. Both failed dismally. Everyone accepts the cliche that people make the organisation – but much more does the organisation make the people. When researchers studied the performance of fund managers in the 1990s, they discovered that just 30 per cent of the variation in fund performance was due to the individual, compared to 70 per cent to the company-specific setting.

E That will be no surprise to those familiar with systems thinking. W Edwards Deming used to say that there was no point in beating up on people when 90 per cent of performance variation was down to the system within which they worked. Consistent improvement, he said, is a matter not of raising the level of individual intelligence, but of the learning of the organisation as a whole. The star system is glamorous – for the few. But it rarely benefits the company that thinks it is working it. And the knock-on consequences indirectly affect everyone else too. As one internet response to Gladwell's New Yorker article put it: after Enron, 'the rest of corporate America is stuck with overpaid, arrogant, underachieving, and relatively useless talent.'

F Football is another illustration of the star vs systems strategic choice. As with investment banks and stockbrokers, it seems obvious that success should ultimately be down to money. Great players are scarce and expensive. So the club that can afford more of them than anyone else will win. But the performance of Arsenal and Manchester United on one hand and Chelsea and Real Madrid on the other proves that it's not as easy as that. While Chelsea and Real have the funds to be compulsive star collectors – as with Juan Sebastian Veron – they are less successful than Arsenal and United which, like Liverpool before them, have put much more emphasis on developing a setting within which stars-in-the-making can flourish. Significantly, Thierry Henry, Patrick Veira and Robert Pires are much bigger stars than when Arsenal bought them, their value (in all senses) enhanced by the Arsenal system. At Chelsea, by contrast, the only context is the stars themselves – managers with different outlooks come and go every couple of seasons. There is no settled system for the stars to blend into. The Chelsea context has not only not added value, but it has also subtracted it. The side is less than the sum of its exorbitantly expensive parts. Even Real Madrid's galacticos, the most extravagantly gifted on the planet, are being outperformed by less talented but better-integrated Spanish sides. In football, too, stars are trumped by systems.

G So if not by hiring stars, how do you compete in the war for talent? You grow your own. This worked for investment analysts, where some companies were not only better at creating stars but also at retaining them. Because they had a much more sophisticated view of the interdependent relationship between star and system, they kept them longer without resorting to the exorbitant salaries that were so destructive to rivals.

Knowledge in medicine

A What counts as knowledge? What do we mean when we say that we know something? What is the status of different kinds of knowledge? In order to explore these questions, we are going to focus on one particular area of knowledge – medicine.

B How do you know when you are ill? This may seem to be an absurd question. You know you are ill because you feel ill; your body tells you that you are ill. You may know that you feel pain or discomfort but knowing you are ill is a bit more complex. At times, people experience the symptoms of illness, but in fact, they are simply tired or over-worked or they may just have a hangover. At other times, people may be suffering from a disease and fail to be aware of the illness until it has reached a late stage in its development. So how do we know we are ill, and what counts as knowledge?

C Think about this example. You feel unwell. You have a bad cough and always seem to be tired. Perhaps it could be stress at work, or maybe you should give up smoking. You feel worse. You visit the doctor who listens to your chest and heart, takes your temperature and blood pressure, and then finally prescribes antibiotics for your cough.

D Things do not improve but you struggle on thinking you should pull yourself together, perhaps things will ease off at work soon. A return visit to your doctor shocks you. This time the doctor, drawing on years of training and experience, diagnoses pneumonia. This means that you will need bed rest and a considerable time off work. The scenario is transformed. Although you still have the same symptoms, you no longer think that these are caused by pressure at work. You know have proof that you are ill. This is the result of the combination of your own subjective experience and the diagnosis of someone who has the status of a medical expert. You have a medically authenticated diagnosis and it appears that you are seriously ill; you know you are ill and have the evidence upon which to base this knowledge.

E This scenario shows many different sources of knowledge. For example, you decide to consult the doctor in the first place because you feel unwell – this is personal knowledge about your own body. However, the doctor's expert diagnosis is based on experience and training, with sources of knowledge as diverse as other experts, laboratory reports, medical textbooks and years of experience.

F One source of knowledge is the experience of our own bodies; the personal knowledge we have of changes that might be significant, as well as the subjective experiences are mediated by other forms of knowledge such as the words we have available to describe our experience, and the common sense of our families and friends as well as that drawn from popular culture. Over the past decade, for example, Western culture has seen a significant emphasis on stress-related illness in the media. Reference to being 'stressed out' has become a common response in daily exchanges in the workplace and has become part of popular common-sense knowledge. It is thus not surprising that we might seek such an explanation of physical symptoms of discomfort.

G We might also rely on the observations of others who know us. Comments from friends and family such as 'you do look ill' or 'that's a bad cough' might be another source of knowledge. Complementary health practices, such as holistic medicine, produce their own sets of knowledge upon which we might also draw in deciding the nature and degree of our ill health and about possible treatments.

H Perhaps the most influential and authoritative source of knowledge is the medical knowledge provided by the general practitioner. We expect the doctor to have access to expert knowledge. This is socially sanctioned. It would not be acceptable to notify our employer that we simply felt too unwell to turn up for work or that our faith healer, astrologer, therapist or even our priest thought it was not a good idea. We need an expert medical diagnosis in order to obtain the necessary certificate if we need to be off work for more than the statutory self-certification period. The knowledge of the medical sciences is privileged in this respect in contemporary Western culture. Medical practitioners are also seen as having the required expert knowledge that permits them legally to prescribe drugs and treatment to which patients would not otherwise have access. However, there is a range of different knowledge upon which we draw when making decisions about our own state of health.

I However, there is more than existing knowledge in this little story; new knowledge is constructed within it. Given the doctor's medical training and background, she may hypothesize 'is this now pneumonia?' and then proceed to look for evidence about it. She will use observations and instruments to assess the evidence and – critically – interpret it in light of her training and experience. This results in new knowledge and new experience both for you and for the doctor. This will then be added to the doctor's medical knowledge and may help in the future diagnosis of pneumonia.

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the text?

- TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

- FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

Questions 6-11

Complete the flow chart below. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the text for each answer.

Combine the , water and other ingredients with a to the desired consistency.

Using the hand, fill with the mixture-coat with (provides a better finish) or water to prevent stickiness.

Dry in the sun; try to avoid rain, which will cause marks in the bricks – this will not affect the bricks'

Transfer to for firing to create the finished product.

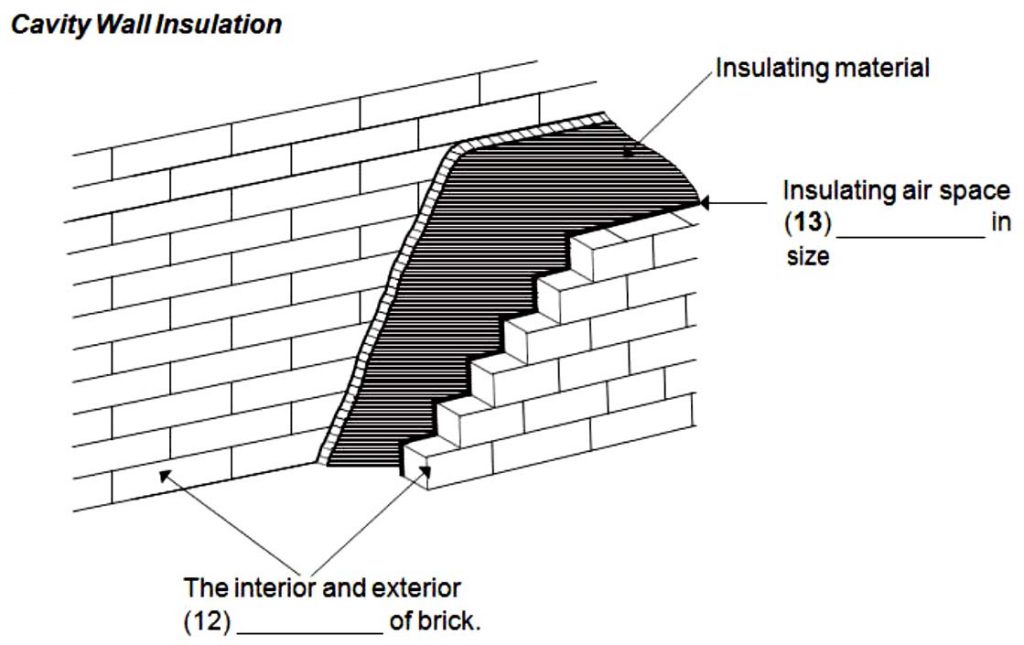

Questions 12 and 13

Label the diagram below. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the text for each answer.

Questions 14-17

The text has seven paragraphs A-G. Which paragraph contains the following information?

NB You may use any letter more than once.

Questions 18-21

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the text?

- YES if the statement agrees with the information

- NO if the statement contradicts the information

- NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

Questions 22-26

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of the text. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the text for each answer.

An investigation carried out on 1000 Participants of a survey by Harvard Business Review found a company hire a has negative effects. For instance, they behave considerably worse in a new team than in the that they used to be. They move faster than wall street and increase their Secondly, they faced rejections or refuse from those within the team. Lastly, the one who made mistakes had been punished by selling his/her stock share.

Questions 27-32

Complete the table. Write NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the text for each answer.

| Source of knowledge | Examples |

|---|---|

| Personal experience | Symptoms of a and tiredness Doctor's measurement by taking and temperature Common judgment from around you |

| Scientific evidence | Medical knowledge from the general e.g. doctor's medical Examine the medical hypothesis with the previous drill and |

Questions 33-40

The text has nine paragraphs A-I. Which paragraph contains the following information?

Results

Score: / 40

IELTS Band: